Roy Kitchener Forth

Roy Kitchener Forth, born November 2, 1915, was the youngest child of Harry and Lucy Forth. My Aunt Irene remembers her Uncle Roy as a fun-loving young man who could play the piano by ear, and loved all sports, especially golfing, bowling and fishing. He had a lot of friends and was always happy according to his family. My dad, Art Prosser, remembers his Uncle Roy as one of his "bed mates" at 54 Waubeek Street in Parry Sound.

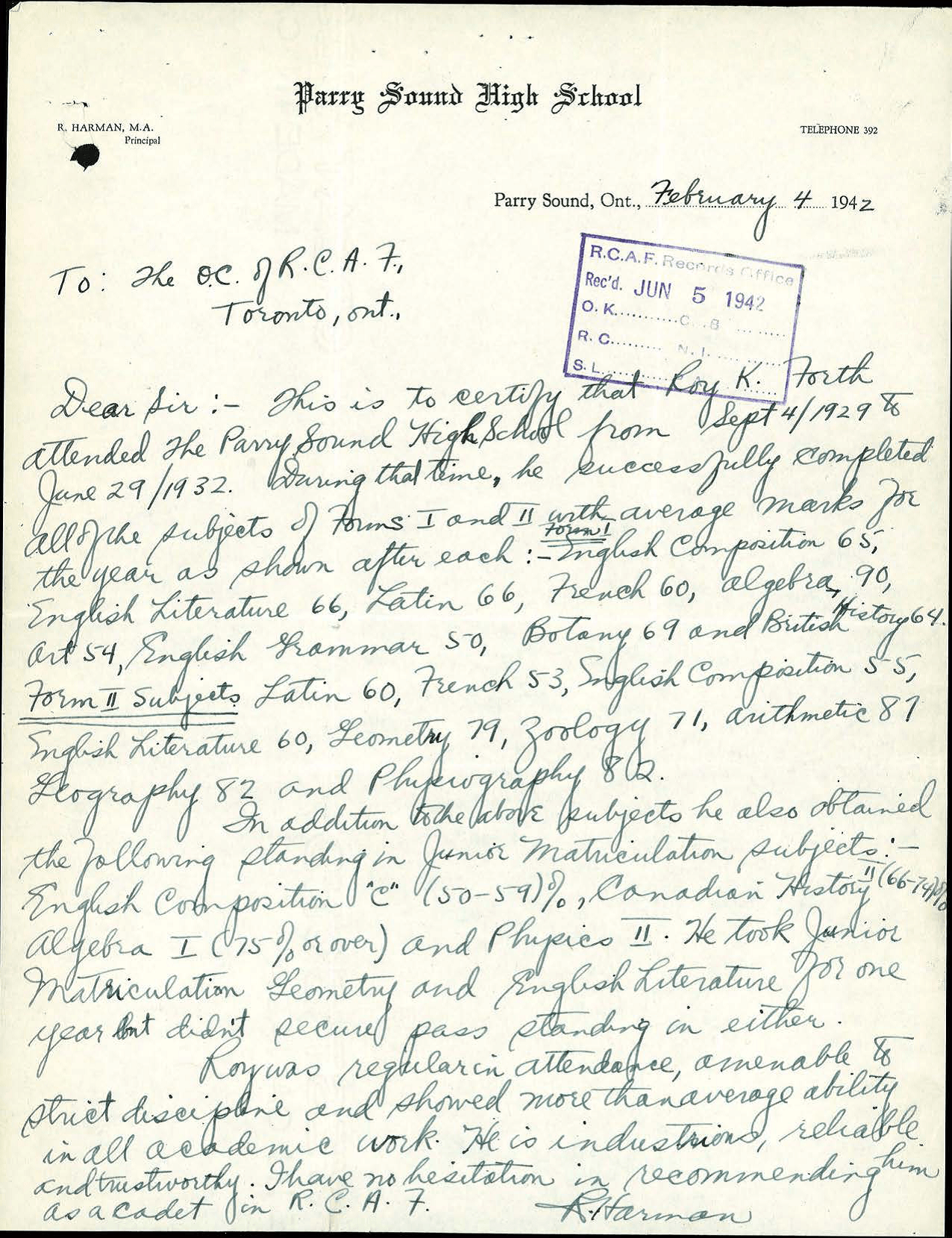

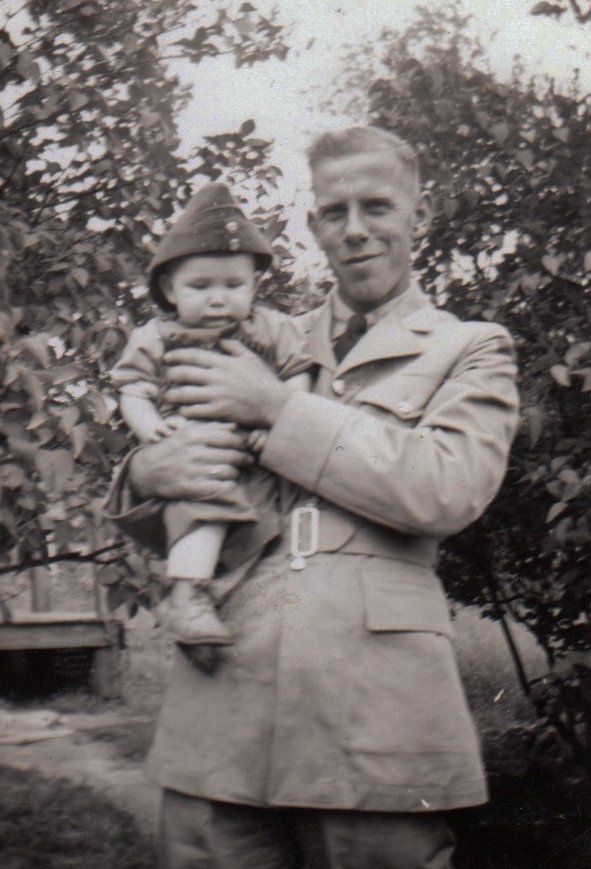

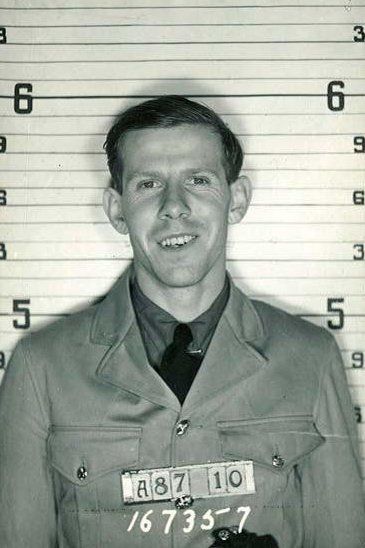

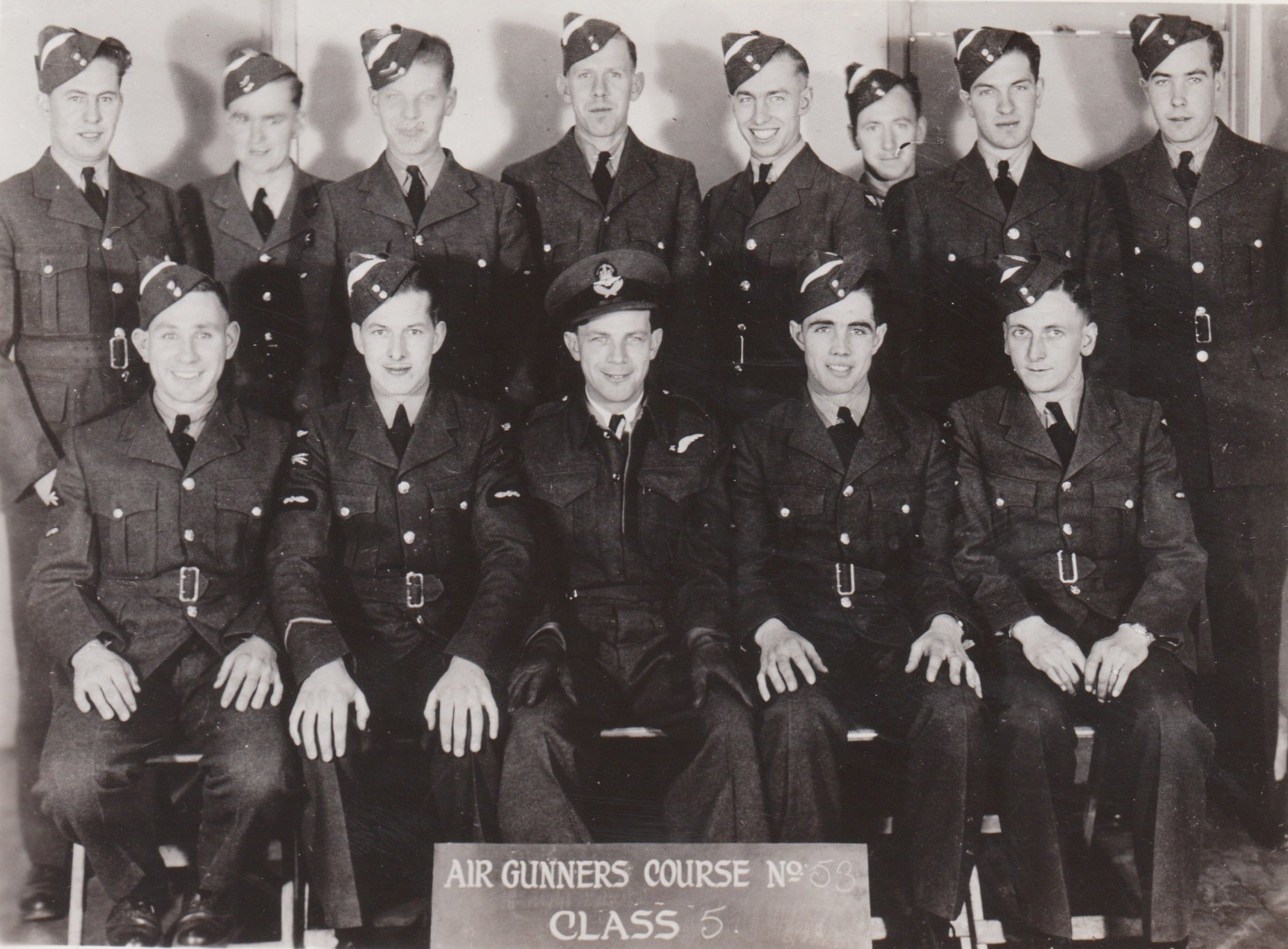

I believe the following photos likely were taken just after Roy enlisted. In one, he is holding his nephew, John Prosser. My Uncle John was born in November of 1941, so these photos look to be in late spring of 1942, likely right after Roy enlisted in May of that year.

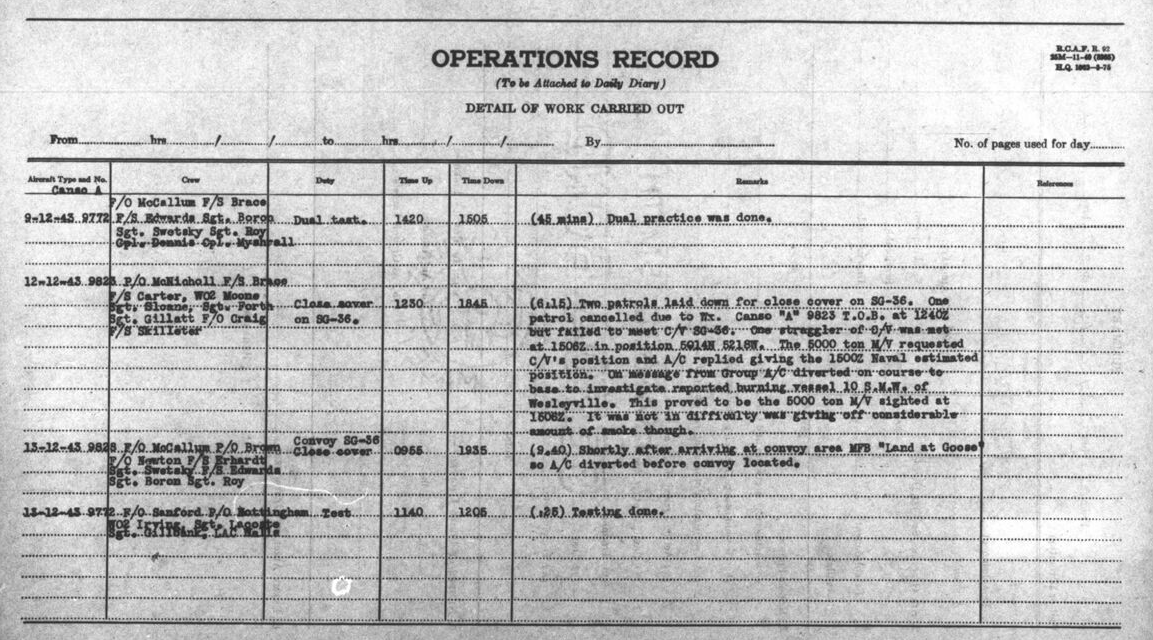

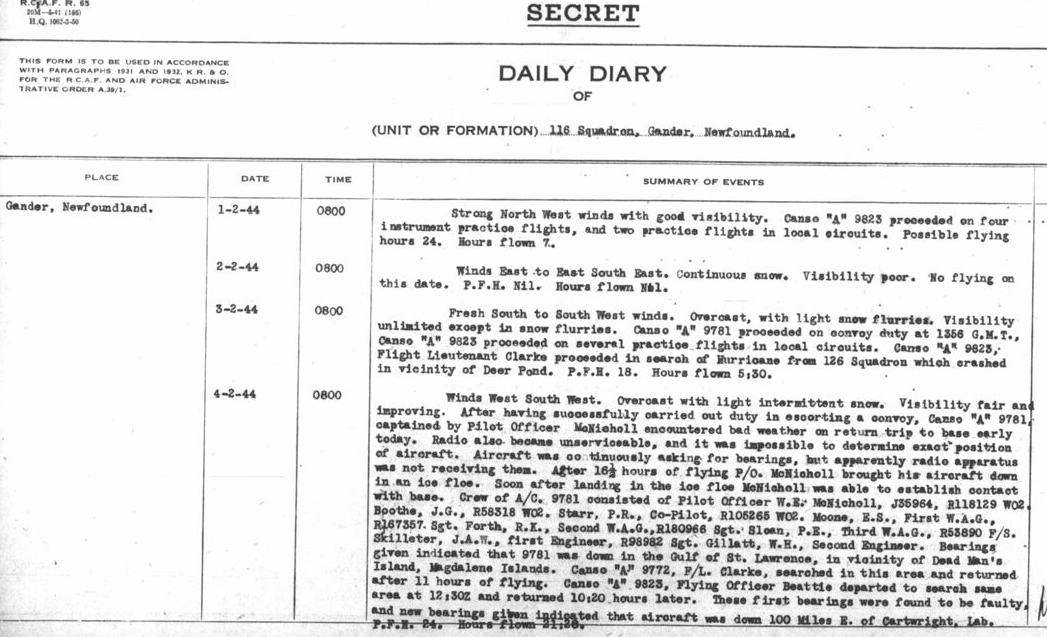

On February 3, 1944, Roy was part of the eight-member crew of Canso "A" 9781, which carried the ID code "Mike". In some records, the aircraft was referred to by its number and in other records it was referred to as the Canso Mike. The aircraft had departed just after 1:30 in the afternoon of February 3 on convoy duty south of Newfoundland and was returning to base, after having successfully escorted the convoy, when it encountered bad weather. The radio only worked intermittently, and it was impossible for the navigator to determine the exact location of the aircraft. The aircraft had continuously been asking for bearings, but its messages were not being received.

At about 4:20 a.m. on February 4, Charlottetown heard the aircraft asking for bearings. Shortly after that, after 16.5 hours of flying, the aircraft was successfully brought down by the pilot, W. E. McNicholl, in an ice floe. Soon after landing, the crew was able to re-establish contact with the base and let them know that they had "Lost balloon and kite". This meant their portable radio was useless. Unfortunately, the crew of Canso Mike didn't know where they were! It was thought the aircraft had landed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence near Dead Man's Island, Magdalene Islands. Two separate rescue planes were dispatched, but neither could locate the downed aircraft. It was determined that the bearings were faulty and a new set of bearings was created which indicated that the aircraft was 100 miles east of Cartwright, Labrador. H.M.C.S. Annapolis was issued orders to set sail for the downed plane.

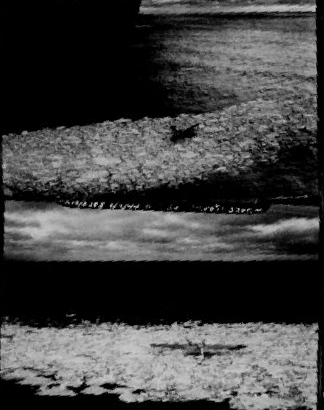

The photos provided of the Canso Mike in the ice floe were part of the Aircraft Accident Investigation Files.

On February 6, Canso "A" 9772 arrived at the site of the downed aircraft about 10:00 a.m. This aircraft was manned by a hand-picked crew and the pilot was the most experienced the 116 Squadron had. The photos that were taken by the Liberator K show that the seas were calm at the time. The pilot asked to land the aircraft but was denied permission by Group 1 Headquarters in St. John's. Instead, he was directed to locate H.M.C.S. Annapolis. Unable to locate the Annapolis, the 9772 returned to the downed aircraft and once again requested permission to land and rescue the crew of the 9781. Permission was refused again.

Word was received that an American Meteorological ship, the U.S.C.G. Conifer, was proceeding to the area of the downed aircraft. It was expected within three hours.

The Canso "A" 9772 was ordered back to base no later than 2100 hours due to impending bad weather. The Liberator K also headed back to base and was too close to home to turn around when it received the instruction that it was to remain with the beleaguered crew as long as possible. They had instructions to "Instruct crew Mike 116 fire pyrotechnics at 2100 and hourly thereafter. Also transmit on Gibson Girl ." This latter instruction was problematic for the crew of the 9781 in any case. The Gibson Girl radio required a hydrogen balloon and box kite to carry the aerial into the air for transmission. The crew had advised base that they had lost their balloon and kite in their first transmission upon landing in the ice floe. The Lindholme Gear had arrived without a replacement Gibson Girl and so there was absolutely no way anyone could contact the crew of the Canso Mike once they left the aircraft and transferred to the dinghies.

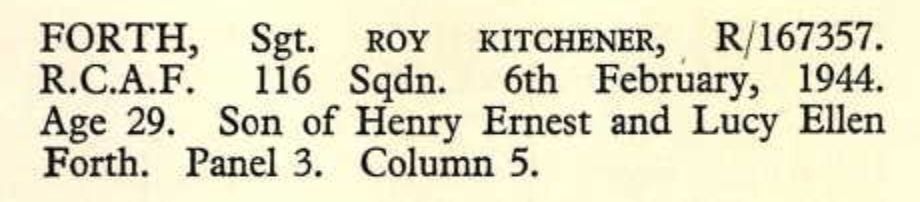

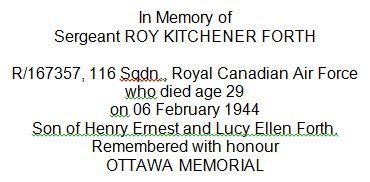

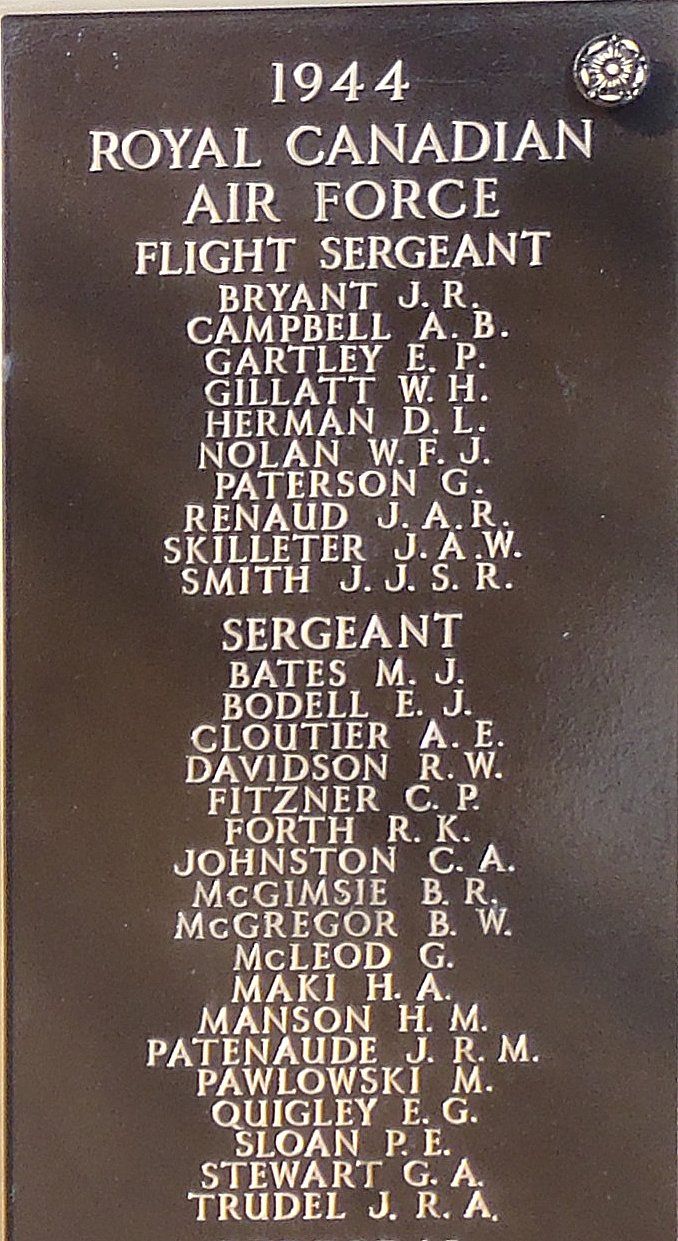

It is believed that all eight crewmen of Canso "A" 9781 perished in heavy seas the night of February 6, 1944, in the North Atlantic Ocean, at a point about 350 miles east of Goose Bay, Labrador and 350 miles north of Gander, Newfoundland.

Although no aircraft were sent out on February 7, due to bad weather in the area of the stranded men, air and sea search operations continued until February 13, 1942.

An inquiry into the accident was held February 4, 1944. After reviewing all the testimony, Air Marshall Robert Leckie concluded, (a) "That the primary cause of the whole affair was bad navigation. The recommendation for better radio compasses is noted, and it is fully agreed that we must take all possible steps to supply these and any other improved navigational aids; but it is not considered that the shortcomings of the present radio compasses caused this accident. Under the apparently bad wireless conditions at the time, it seems doubtful whether any radio compass would have saved the situation; and a well calculated D.R. course should have brought the aircraft close enough to home to make use of all short-range navigational aids. Even with changing winds, no aircraft with a starting point S.E. of Newfoundland and heading for Gander, should end by landing far out into the Atlantic off the coast of Labrador."

Leckie further noted that (b) there was some confusion in the management of the search and that (c) inadequate steps were taken to bring the surface vessels to the site of the downed aircraft.

There is some confusion for me as to how the final report for Section (d) should read. There appear to be two almost identical reports made by Robert Leckie, one which seems to be dated April 3, 1944, and one which seems to be dated April 8, 1944. In the former, Leckie reported that the decision to land a rescue aircraft should have rested on the shoulders of the pilot who was at the scene, not headquarters, as the pilot had the best knowledge of whether or not the landing could be made safely. He also remarked that for the sake of morale it was "better for crews to feel that if they were in peril, bold efforts will be made to save them." However, in the second report, Leckie reported that "your decision not to allow the captain of Canso "K" (sic) to land is supported." The only difference between the two reports is Section (d). It appears that Leckie wrote two different versions of the report which come to two different conclusions.

In Section (e) Leckie wrote that a "Gibson Girl" radio should likely have been sent to the men in the event that they had to ditch the Canso and take to the dinghies - which they eventually did! They then had no radio contact at all.

Leckie concluded his report by saying that (f) "It is not thought that the investigation was well conducted." Nonetheless, he believed that the correct facts had been unearthed and it was upon those facts that he had based his comments.

The problems with the investigation centred around the order, or perhaps the lack of logical order, of the testimony of the witnesses and also the fact that the Investigating Officer used too many leading questions when interrogating the witnesses. There seems to have been a disagreement among the ranks as to whether or not the Canso "A" 9772 should have been allowed to land. In the end, it was the considered opinion of the Air Force that the Eastern Air Command functioned well and that loss of the crew of the Canso Mike was a matter of extreme misfortune. Perhaps Robert Leckie's second report then became the official version. It is indeed the one he signed.

(Many thanks to Dennis Burke of www.ww2irishaviation.com for links he provided to the Operations Record Book and

Aircraft Accident Investigation Files and for his help in "getting the story right".)

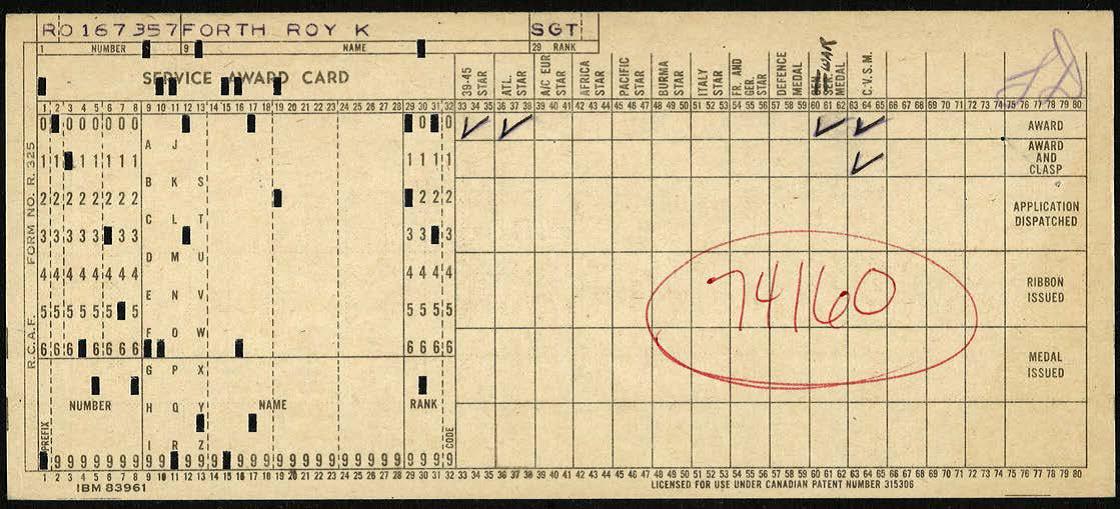

Roy was awarded the following medals according to the Service Award Card below:

1939-45 Star

Atlantic Star

1939-45 War Medal (without oak leaf)

C.V.S.M. (Canadian Volunteer Service Medal) with clasp or bar.

The medals were sent to Roy's eldest brother, Fred Forth, on March 17, 1950. It appears as though the medals may have been lost over time as nobody in the family seems to know where they are.

As with his brother, Frank, more war records exist for Roy than other records and it is sad that those are the things that live on, rather than what Roy brought to the world. He didn't marry and, to my knowledge, fathered no children. I am happy to be able to honour his memory.

Thank you to Harold Shortt who provided assistance with military records.